As published in Tehelka Magazine, Volume 9 Issue 35, Dated August 27, 2012. Reports Tehelka jouranist Prakhar Jain

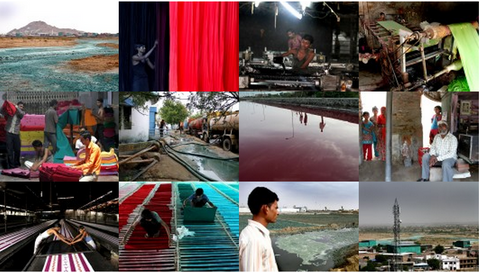

A Rs 5,000 crore textile industry is leaching a desert river in Marwar with chemicals, even as the ground water for villagers plummets.

The color of the river Luni has turned Blue due to contamination that is mostly Indigo dye

The town of Balotra, In Rajasthan’s Barmer district, is known for its textile industry that is engaged in processing the fabric used in making gowns, petticoats and lining material for thin clothes. The units supply textiles across India and to many west-African and neighbouring countries of India. The industry processes more than 1,800 million metres of cloth every year. But over the past few years, the town is gaining notoriety for the coloured riverbed of Luni.

According to the people of the town, the river last flowed with natural rainwater in the 1990s. After that, because of successive droughts, it has never seen any water apart from the effluents discharged in it by the textile units of the town.

River Luni originates in the Pushkar valley of the Aravalli Range, near Ajmer, where it is known as Sagarmati. It then flows southwest, to the Marwar region, entering a patch of desert, before disappearing into the marshes of the Rann of Kutch in Gujarat.

Bleeding chemistry (L to R) A worker pours dye for printing; laying out the dyed fabric to dry; water, treated in the CETPS, is still stained with dye

Elders of Balotra remember farmers growing crops on the banks of the river using tube-wells. Narayan Chelaji (44), a farmer, says, “We used to grow wheat and bajra in our farms, but the water level has gone down, from 20 ft in the past to more than 200 ft. Now, we are dependent on the seasonal rains for whatever little we want to cultivate. Else, nothing grows here.”

Textiles being printed in a printing unit : photo by Vijay Pandey for Tehelka.com

So, how exactly was the river killed?

The textile business in Balotra first started as a household tie-and-dye industry, practised by Muslim communities, from the 1950s onwards. Slowly, other communities picked up the trade and began processing textiles in huge quantities. When the industry started growing in size, the Rajasthan State Industrial Development and Investment Corporation Limited (RIICO), brought them together in an industrial area in 1975. From then on, the processing units have constantly increased in number over time, through phase II and III of the industry being established in 1983 and 1995 respectively.

After the third phase was established in 1995, the total number of units increased from 180 under phase I, to 400 under phase III, in Balotra alone. During that period, the industries also saw a major shift in the use of chemicals. Instead of natural vegetable dyes, chemical dyes began to be used by the industries to meet the increasing demand. The repercussion was the increase in the demand for water to process the raw fabric. Thus, a need for alternate, water-abundant area was felt and the nearby villages of Jasol and Bithuja filled the gap.

All the 214 textile-units in Bithuja are engaged in water intensive pre-processing of fabric. The dyeing and printing still takes place in Balotra. The units in Jasol, however, have emerged as a parallel industrial hub with all the facilities under one roof.

THE BALOTRA Water Pollution Control and Research Foundation Trust was established in 1995, to check pollution in the river. The trust established two common effluent treatment plants in Balotra and one in Bithuja. One water treatment plant was also established in Jasol, which caters to around 70 units and is run by a separate trust formed by the units operating there.

But over time, wastewater production has increased so much that the existing treatment plants are unable to treat all the effluents from these industries. Few units, which have been established to process synthetic fabrics, have further worsened the problem by discharging oil and grease along with the sludge.

In 2004, the Rajasthan High Court, responding to a Public Interest Litigation issued a set of directions to the state environment department saying, “the industrial units that are discharging the industrial pollutant on the land and river shall be closed forthwith.”

The court also ordered the state government to make an assessment of the extent of pollution so as to decide on the question of payment of compensation by the units on the principle of ‘polluter pays’. The report was commissioned and was submitted by the National Productivity Council (NPC) in 2010.

The NPC reported that the ground water in the region is “unpotable” because of high Total Dissolved Solids (TDS), which are basically dissolved salts, and added that there is low concentration of soil nutrients in the polluted areas, a “manifestation of the adverse impact of discharging textile effluent in the river.” Commenting on the situation Nazimuddin, a senior scientist at the Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB), says, “This is a common phenomenon, as you go deeper, the TDS increases. TDS and water availability are a problem when you have such industries in large numbers.”

After studying the various parameters for water, the NPC report also suggested that “the ground water contamination has occurred only recently due to the mushrooming of new industries in these regions” and “if groundwater is used for irrigation purposes then it will have a damaging impact on the fields”.

The report says that the Common Effluent Treatment Plants (CETPs) at Balotra, Jasol and Bithuja, are not able to handle the entire wastewater received by them and a significant portion was being discharged directly into the river Luni, bypassing the treatment system. Thus, the experts who prepared the NPC report recommended that no more expansion or setting up of new units be permitted until all the CETPs are upgraded.

However, the directions of the court were not complied with in full and the units continued to function. In February 2012, the HC passed an order directing the Rajasthan Pollution Control Board (RPCB) to ensure that the units attain zero discharge from their effluent treatment plants and again ordered the units to stop releasing any wastewater in the river. The HC was responding to a PIL filed by, Digvijay Singh, a Jodhpur based advocate.

A day later, the RPCB ordered shutting down of all the industries in the region. Suddenly, close to 30,000 people lost direct employment, while a similar number of people were affected indirectly. The industry, with an annual turnover of more than Rs 5,000 crore, came to a grinding halt.

After remaining closed for almost three months, the industry decided to reduce its production by 60 percent and regulate its water consumption. Thus, a calculated quantity is now supplied to each unit by tankers and the effluents are transported to the treatment plants in a similar way. Roopchand Salecha, president of the Balotra Laghu Udhyog Mandal and also the chairman of the Balotra Water Pollution Control and Research Foundation Trust, says, “We pay Rs 1,000 to transport 20,000 litres of water, and Rs 800 to send the effluents to the treatment plant. An additional Rs 60 per bale of raw material is also collected by the trust to keep the effluent treatment plants running.”

The effluents, however, instead of being recycled, are released in a 276 bigha land that was acquired a decade ago for horticulture, using the treated water.

Salecha claims that the TDS in groundwater is too high to be brought down to prescribed standards. “How can they expect us to use the water with a TDS of over 20,000 ppm and then bring it down to 2100 ppm? Even the municipal water supplied for drinking here has a TDS of more than 5,100 ppm,” he says. He, however, says that there are two new treatment plants and a reverse osmosis (RO) plant under construction in Balotra and Jasol that would address the present concerns.

A survey by the Central Pollution Control Board on the water consumption and sewage generation in the town claims, the textile units of Balotra use five times more water than that supplied to the entire population of the town. The per capita water supply in Balotra is just 66 litres per day, less than one-fourth the quantity supplied in cities like Delhi and Mumbai.

More than 10,000 workers have been affected directly and indirectly after the Rajasthan Pollution Control Board cracked down heavily on the units to comply with the court order

So what is the alternative to this pollution? Digvijay Singh says that if the industries are to run at all, they should first clean up the river and attain zero-discharge. “The NPC has estimated that the economic value of the damages caused by the textile industry in Balotra, Jasol and Bithuja in the past 15 years is more than Rs 76 crore. The units should pay compensation to farmers first and clean up the river,” he says. He also points out that units in Bithuja and Jasol are not situated in the industrial area and are therefore illegal.

The NPC report has detailed out steps that can be followed by the industries, CETPs, pollution control board and other stakeholders concerned to reduce pollution. One of them is that the wastewater be treated to such an extent that it meets the irrigation water quality standard.

For now, the industrialists are staring at the huge construction cost of the RO plant. The plant is to cost approximately Rs 60 crore and is to be mostly funded by grants from the Centre and the state. The file is currently awaiting clearance from the Ministry of Environment and Forests.

Nazimuddin, a senoir scientist from the CPCB, says, “CETP standards were declared some 20 years back, but most of the states have been ignoring it. The Tamil Nadu board took the initiative and installed equipment for total dissolved solids (TDS) control that included expensive technology like RO too. But now, Rajasthan will also have to take measures. Not only this, they will have to rethink about the water intensive industries in such areas.”

Photo credits: Vijay Pandey for Tehelka.com